WRITINGS

Below you will find recent work of mine from a variety of journals, websites, and reviews.

Are We Comfortable Encountering Strangers Anymore?

Published in LITHUB

Beyond Repair is told through a series of encounters with friends and neighbors, colleagues and strangers, from early 2014 to spring 2019. It’s the story of my re-emergence after surviving and recovering from a major car accident. When I finally returned to the world—as father and husband, friend and brother—it became clear that we were all trapped in a traumatized state—reeling from one after another police shooting of unarmed African-Americans, stunned by yet another mass shooting—and that everywhere people were displaying signs of PTSD.

My interactions in daily life became more and more dysfunctional—us against them, red vs. blue, rich vs. poor. That my family and I live in Asheville, NC—a progressive town inside a conservative county in the mountain South—only made things more volatile.

I tried to enter into these experiences as conscious as possible of the potential divides and misunderstandings between us—including my own unearned privilege as a middle-aged white man—while working to make meaningful connection. I started close by then traveled out into the wider world. At the same time, we were raising our teenage boy, doing our best to help him navigate this new, challenging environment.

White Men in Trucks

What is it about them that shoots a brief goose of fear into my bloodstream? Is it imminent threat sounding in the revved engine? Derision caught in the side-view mirror? Or plain old disdain drumming its fingers on the drivers’ side door? A little of each!? All I know is I am walking through our suburban neighborhood, and a truck barrels past, not slowing nor moving over. That another swerves around the bend, almost clipping my dog, meeting my upraised hands with a jutting middle finger. And another drives right up behind me and rides my bumper all the way up the hill.

Just landed at JFK, about to head into Manhattan for the first time in over a year. Instead of flagging a cab or jumping into a van, I follow the signs to the AirTrain, three stops to the A-line, joining a huddle of men and women on the cold and grey platform, wind shuttling in.

What about that cold embrace speaks to my bones? What about this congress of strangers?

The whole ride, letting the wider world in, not looking up, just listening to the bodies around me settle into the silence. Only glances allowed, brief encounters with faces. Train car slowly filling. Dipping down into the long dark tunnel.

A young man enters the car and introduces himself. “I’m not here to bang you or bore you,” he sing-songs, “I’m here to sing to you, brothers and sisters.”

Of course, no one looks up; nothing spectacular in this scenario. Though the man beside me leans down and opens his stance a notch, turns his face to hear our singer, nodding as he climbs the verbal steps up onto his soap-box. “I don’t do R & B. Don’t do Rap.”

All I see for now are his red sneakers, his nervous strut back and forth. “People, I sing gospel.”

The train pushes further through Queens.

This young man’s flock heads into their days, wrapped up in headphones and handhelds, but I can feel the car tune into the sweet singing. “There is no friend like Jesus,” he belts. The congregant beside me nods a fraction.

We’re approaching a stop. The song is through. There’s a moment to ad-lib, so a brief bio gets offered up: “I’m only 26. I’ve banged and boozed. I’ve seen it all.”

My seatmate slips a few coins into the man’s hand as he offers up a little fist pump of thank you. A tired-looking transwoman watches me as I watch the young man, who adds, “I’ve been shot three times,” and someone laughs out loud at the back of the car.

This makes our young pastor smile, and he turns to engage the commentary. I want to give the man a dollar, to offer up some thanks of my own. But I stop myself, not wanting to make my first overt act in the City be reaching for bills in a tight front pocket.

The man drifts off to his next stage. My seatmate gets off at the next stop. The car fills with a new surge and in the next length of time I give my thanks by humming quietly in my body, letting in as much as I can, offering praise to this daily gathering of bodies, faces, lives, glances, mute stares. “I’m here to sing,” the young man said.

It makes me want to cry. But I lower my head instead and fall deeper into my seat, letting the woman beside me settle into my shoulder. Soon, we’ll be under the river and I’ll step out into the great canyons of wind and light.

But, for now, here, I will quietly sing into my own breath.

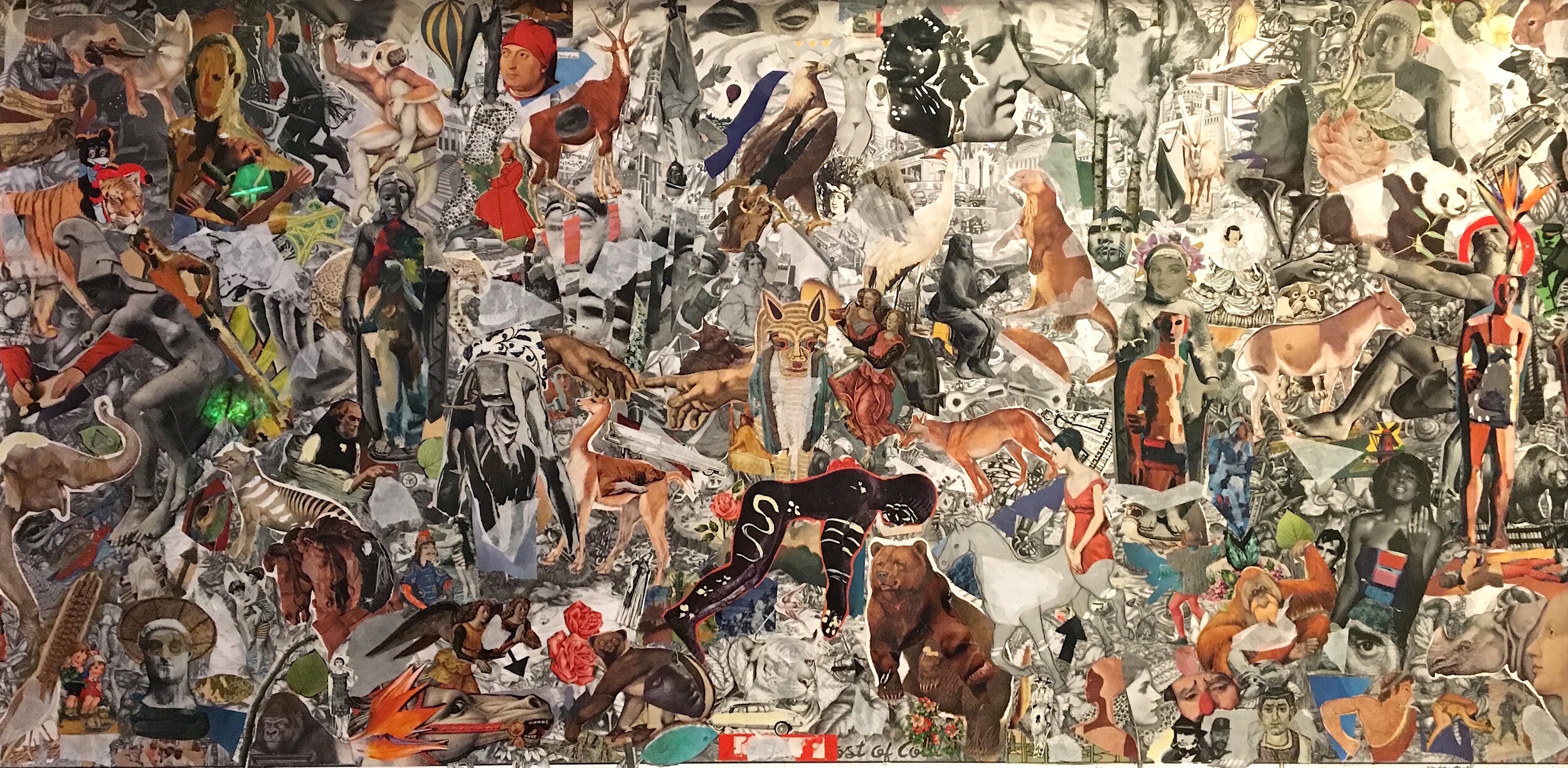

From BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson (1943-1967) Design, Sebastian Matthews, Bill Matthews Print, Brandon Mise, Blue Barnhouse Press

“Messages in a Bottle: Notes of an Unlikely Curator” - Blackbird Archive - Vol 9. No 2.

[An Excerpt]

You are going to find that studying Ray becomes a discovery of yourself . . . yet also a revelation of yourself to others.

—William S. Wilson

This remark came at a point early in my correspondence with Bill Wilson, a scholar and art collector and longtime friend of Ray Johnson. Because it came both at the beginning of one of his emails and early in the curatorial process, I read it as a warning—a little wisdom from a longtime expert in the field, a curmudgeon’s scold directed at a first-time curator blithely sauntering in. A polite but firm, Don't mess this up, kid.Wilson was right to warn me. A lot goes into putting together an exhibition, and the task only gets more difficult with an artist like Ray Johnson. The people who collect Ray’s work all have a unique and complicated relationship to the artist. Many of them were his friends, supporters, fellow Black Mountain College students; most want to preserve his legacy and, therefore, despite their generous lending, approached the process with trepidation. Ray’s famously ambivalent attitude toward exhibitions and the art “biz” in general added a whole new layer to the project.

My own sense of Ray Johnson as an artist (and how his work will be considered in the future) was tentative, evolving. No longer do I think of Ray’s famous bunny heads and his mail-art envelopes as definitive trademarks of his work, viewing them, instead, as buds blossoming at the tip of a branch of the flowering tree. Now it's Ray's early love of letter writing and doodling, his dramatic move away from painting—his fascination with glyph markings, cutting up things, his verbal and visual reversals, his incessant punning—that exemplify the fundamental nature of his work….